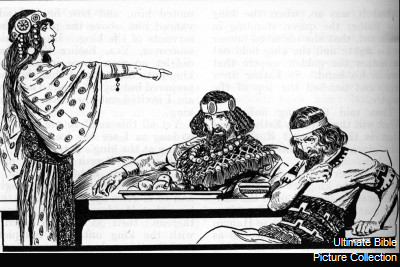

“As

the word went out of king's mouth, they covered Haman's face”.

“Amon was twenty-two years old when he

became king, and he reigned in Jerusalem two years. He did evil in the eyes of the Lord, as his father Manasseh had done.

Amon worshiped and offered sacrifices to

all the idols Manasseh had made. But unlike his father Manasseh, he did not humble himself before the

Lord; Amon increased his guilt”.

2 Chronicles

33:21-23

“Amon …. His mother’s name was Meshullemeth daughter of Haruz; she was

from Jotbah. …. Amon’s officials conspired against him and assassinated the

king in his palace.

Then the people of the land killed all who had plotted

against King Amon …”.

2 Kings 21:19,

23-24

Introductory

A notable feature of the extremely brief biography

of king Amon of Judah, as given above in 2 Chronicles and 2 Kings, is that one

so young as he, in his early twenties, whose reign was so short, seemingly,

“two years”, could have outdone in wickedness his father Manasseh, who reigned

for “fifty-five years” (2 Kings 21:1), and who was - according to the prophet

Jeremiah - a very cause of the Babylonian catastrophe that was then about to

befall Jerusalem and the Jews (Jeremiah 15:4): “I will make them

abhorrent to all the kingdoms of the earth because

of what Manasseh son of Hezekiah king of Judah did in Jerusalem”.

Jeremiah’s statement here immediately prompts a

further consideration.

Why would

the prophet single out Manasseh, by now supposedly well dead, when other evil

kings of Judah would fill in the gap between Manasseh and the Babylonian incursions?

Prior to the Fall of Jerusalem certain idolatrous

progeny of king Josiah of Judah would reign: namely, (i) Jehoahaz; (ii) Eliakim

(re-named Jehoiakim); (iii) Jehoiachin; and (iv) Mattaniah (re-named Zedekiah).

Also in need of explanation is the testimony of 2

Chronicles that “Amon increased his guilt”. “Two years” of

reign might seem hardly enough time for one notably to “increase” one’s guilt, at

least to the extent that it would be considered worth mentioning.

There

must be more to this King Amon of Judah than meets the eye!

The solutions to be proposed in this article will

serve to solve not a few problems – although they will cause new ones as well.

The positives, however, will well outweigh the negatives.

Part One:

Amon

during the Babylonian Era

Duplicate

Kings of Judah

Amon’s royal alter ego

It is rather unfortunate that so little is known of

the reign of Amon, king of Judah; for he lived evidently in a critical period.

The endeavors of the prophets to establish a pure form of YHWH worship had for

a short time been triumphant in Hezekiah's reign; but a reaction against them

set in after the latter's death, and both Manasseh and his son Amon appear to

have followed the popular trend in reestablishing the old Canaanitish form of

cult, including the Ashera and Moloch worship. Whether Manasseh

"repented," as the chronicle tells us, is more than doubtful. There

is no record of this in the book of Kings, and absolutely no indication of such

a change in the subsequent course of events. ….

{The repentance of Manasseh is

yet another issue that we intend to address in this article}.

Above we read that at least two of Josiah’s sons,

Eliakim and Mattaniah, were re-named.

The same, we think, must have applied to King Amon,

for this name “Amon” is not Hebrew, but is the name of the Egyptian “king of

the gods” Amon (also Amun, Amen, Ammon).

|

|

It is found, for instance, in the name Tutankhamun.

“Living Image of Amun”

|

The first step in our search for the complete King

Amon (Part One) could therefore be to find an initial alter ego for him. And the likeliest

possible alter ego for Amon among the

evil later kings of Judah is the similarly short-reigning Jehoiachin, an

historically-attested king.

Amon-as-Jehoiachin offers the two immediate

advantages of this king’s:

(i) having gone into Babylonian

captivity and continuing on there for about four decades (Jeremiah 52:31) –

thereby enabling for him to have, as is said of Amon, “increased his guilt”;

and

(ii) having as his father one

Jehoiakim, who - since the latter was appointed and re-named by pharaoh Necho -

was an Egyptian vassal - hence providing an

explanation for why his son Jehoiachin might also have the Egyptian name

Amon.

Whilst, admittedly, Jehoiachin’s age and length of

reign in Jerusalem (2 Kings 24:8): “Jehoiachin was

eighteen years old when he became king, and he reigned in Jerusalem three

months”, do not perfectly

match those of Amon (“twenty-two years” of age and “two years” of reign) - one

of those newly-created problems referred to above - the differences can largely

be accounted for by co-regency.

Indeed, a calculation of the reigns of Jehoiakim

and his son, Jehoiachin, in relation to those of the contemporaneous Babylonian

(Chaldean) kings will bear this out. The

most important date in the Old Testament, synchronising two biblical kings

with a secular king, and also including a number for Jeremiah, is this one from

the Book of Jeremiah (25:1-3):

The

word came to Jeremiah concerning all the people of Judah in the fourth year

of Jehoiakim son of Josiah king of Judah, which was the first year of

Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon. So

Jeremiah the prophet said to all the people of Judah and to all those living in

Jerusalem: ‘For twenty-three years—from the thirteenth

year of Josiah son of Amon king of Judah until this very day—the word of

the Lord has come to me and I have spoken to you again and again, but you

have not listened’.

Since Jehoiakim’s 4th year corresponded

to the 1st year of King Nebuchednezzar II, then Jehoiakim’s last

year in Jerusalem, his 11th (2 Kings 23:36): “ Jehoiakim

was twenty-five years old when he became king, and he reigned in Jerusalem

eleven years”, must correspond to Nebuchednezzar’s 8th year of reign.

Jehoiachin then succeeded his exiled father,

Jehoiakim, as king in Jerusalem.

It is commonly agreed that Nebuchednezzar II reigned

for 43 years, which would mean that, by the end of his reign, 35 years after

Jehoiakim’s exile, in the 1st year of Nebuchednezzar’s son-successor,

Evil-Merodach,

(i) Jehoiakim would be in about

his 46th year, whilst

(ii) Jehoiachin would be in about

his 35th year.

However, according to Jeremiah 52:31, Jehoiachin

was then in his 37th year: “And in the thirty-seventh year of the exile of Jehoiachin king of Judah, in

the twelfth month, on the twenty-fifth day of the month, Evil-merodach king of

Babylon, in the year that he began to reign, graciously freed Jehoiachin king

of Judah and brought him out of prison”.

That two-year discrepancy (35th, 37th)

is just the amount of co-regency required - if we have properly calculated it -

for an accurate merging of the reign of Amon with that of Jehoiachin.

Perhaps more difficult to explain is the apparent

discrepancy in the case of the “mother”.

Compare these two texts:

“[Amon’s] mother’s name was Meshullemeth daughter of Haruz; she was from

Jotbah” (2 Kings 21:19).

“[Jehoiachin’s] mother’s name was Nehushta

daughter of Elnathan; she was from Jerusalem” (2 Kings 24:8).

Different names, different geography!

But “mother” can have a somewhat broad meaning, not

always intending biological mother.

It can also refer to the Gebirah, גְּבִירָה “the

Great Lady”, who can be the grand-mother.

“Gebirah =

grandmother

Maacah, 1 Kings 15:8-24 ...”. (Agape

Bible Study)

I Chronicles 3:16

seems to have Zedekiah, the uncle of Jehoiachin, as the latter’s brother.

We shall return to this in Part Two when we

further extend Amon as a captive in a foreign land, where we shall find him

designated as a “son of” his actual aunt,

and not his mother.

Manasseh’s royal alter ego

With Amon now tentatively identified as Jehoiachin,

we turn to consider the possibility (already alluded to above) that Amon’s

father, Manasseh, was the same as Jehoiachin’s father, Jehoiakim. This new

identification, whilst seeming to solve a host of problems, does, once again,

create new ones, such as the need now to re-arrange the list of late Judaean

kings. And this will, in turn, affect a part of Matthew’s “Genealogy of Jesus

Christ”.

Advantages

of this identification

It would immediately explain why Jeremiah would

attribute the Babylonian catastrophes to Manasseh, instead of to a supposedly

later idolatrous king of Judah, such as Jehoiakim.

For, if Manasseh were Jehoiakim, as we are thinking, then that problem simply

dissolves.

From 2 Kings 24:6 it appears that King Jehoiakim,

though taken into captivity in chains, had actually died in peace. That would

accord nicely with the biblical testimony that Manasseh finally repented

(“humbled himself before the Lord”), returned to Jerusalem, then rebuilt and

fortified the capital city (2 Chronicles 33:14).

From the above calculations for Jehoiakim in

relation to the Babylonians, his alter

ego, Manasseh, would have been, with the advent of the Medo-Persian era, in

about the 50th year of his 55 years of reign.

Twelve years old at the commencement of his reign

(2 Kings 21:1), now plus 50.

We might even be able to identify him with the

mysterious “Sheshbazzar the prince of Judah” of Ezra 1:8, into whose hands

Cyrus gave “the

treasures that Nebuchadnezzar had taken”.

{Was “Sheshbazzar”

also the “Shaashgaz” of Esther 2:14?}

King Manasseh would have died only a few

years after this famous Ezra 1:8 incident.

Again we ask: What

about that very strong tradition that the prophet Isaiah was martyred during

the reign of King Manasseh? There is nothing in the Bible to indicate that

Manasseh, under this name, had martyred Isaiah. Might we, though, find the

incident in the account in which his alter

ego (as we think), Jehoiakim, had a fleeing prophet pursued into Egypt

(Jeremiah 26:20-23)? The prophet is there named “Uriah” (or Urijah), which name

is, in its variant Azariah, compatible with “Uzziah” (Isaiah’s name in Judith -

see next page).

{King Uzziah of Judah: 2

Chronicles 26:1, was also named Azariah: 2 Kings 15:1)}.

Seal of

the prophet Isaiah?

We know this of “the great prophet Isaiah” from

Sirach 48:24-25: “His powerful spirit looked into the

future,

and he predicted what was to happen before the end of time,

hidden things that had not yet occurred”. His foretelling of Cyrus (e.g. Isaiah

45:1): “Cyrus is my anointed [“messiah”: מְשִׁיח] king”, is one such case, and, owing to

Isaiah’s propensity for predicting hidden and distant things, commentators must

scramble to create a Deutero-, even a Trito-Isaiah. Chances are, though, that,

according to our revision - which shunts the age of Isaiah (and the late

neo-Assyrian kings) right into the age of Isaiah’s younger contemporary,

Jeremiah (and the neo-Babylonian kings) - Cyrus was already a teenager by the

time of the reign of Jehoiakim; the reign that bore the burden, as we think, for

Isaiah’s martyrdom.

Cyrus may

therefore have been known to Isaiah as a young prodigy, perhaps, for instance

under the tutelage of Ahikar, nephew of Tobit, a governor of Elam (Susa) from

where Cyrus would one day reign. Ahikar had previously been the mentor of

Sennacherib’s eldest son, the treacherous “Nadin” (Nadab) of Tobit 14:10, and

the “Holofernes” of the Book of Judith.

Ahikar and Isaiah had met at least once, in the

midst of the Judith drama, Ahikar as “Achior”, and Isaiah as “Uzziah son of

Micah, of the tribe of Simeon” (Judith 6:15).

Now, regarding the king’s mother’s name, which had

loomed as somewhat awkward in the case of Amon-Jehoiachin, Manasseh’s “mother's

name … Hephzibah” (2 Kings 21:1)

stands up quite well against Jehoiakim’s “mother's name … Zebudah, the daughter of Pedaiah of Rumah” (2 Kings 23:36). Thus, Zibah and Zebudah.

We read above that Jehoiakim was taken into

Babylonian captivity in chains, and so, too, was Jehoiakim’s alter ego, Manasseh (2 Chronicles

33:11): “So

the LORD sent the commanders of the Assyrian armies, and they took Manasseh

prisoner. They put a ring through his nose, bound him in bronze chains, and led

him away to Babylon”. “'Manasseh King of

the Jews' appears in a list of 22 Assyrian tributaries of Imperial Assyria on

both the Prism of Esarhaddon and the Prism of Ashurbanipal" (E.M.

Blaiklock and R.K. Harrison, The

New International Dictionary of Biblical Archaeology, 1983)”.

The approximately 43-year reigning Ashurbanipal

(c. 669 - c. 626 BC, conventional dating), contemporaneous

with Manasseh, must therefore be the same as the 43-year reigning

Nebuchednezzar (c. 605 - c. 562

BC, conventional dating), contemporaneous with Jehoiakim.

As with

Jehoiakim’s death, apparently, so was Manasseh’s passing peaceful (2 Kings

21:18): “And Manasseh slept with his fathers, and was buried in the garden of

his own house, in the garden of Uzza”. This unknown location, presumed to be

somewhere in the city of Jerusalem, is where we shall learn that Amon, too, was

buried.

And we shall find

that it was not in Jerusalem but was in the land of exile of these two kings.

Hezekiah’s royal alter ego

Hezekiah

trusted in the LORD, the God of Israel. There was no one like him among all the

kings of Judah, either before him or after him. He held fast to the LORD and

did not cease to follow him; he kept the commands the LORD had given Moses.

Neither

before nor after Josiah was there a king like him who turned to the LORD as he

did—with all his heart and with all his soul and with all his strength, in

accordance with all the Law of Moses.

How

can the reigns of Hezekiah and Josiah both be the greatest, especially when it

is said of both that neither before nor after him was there a king like him? Is

this a contradiction?

[End of quote]

This is an excellent question, and our proposed

answer to it is that Hezekiah and Josiah were equally great, because Hezekiah was Josiah.

Once again, this new suggestion will have its

advantages, but will also create its problems – some of these being rather

severe. For instance, according to various scriptural texts as we now have them

(e.g., 2 Kings 21:25-26; 2 Chronicles 33:25; Zephaniah 1:1; Matthew 1:10),

Josiah was the son of Amon, who, in turn, post-dates Hezekiah.

This is how (our current) Matthew 1 sets out the

relevant series of kings of Judah (vv. 9-11):

…. Ahaz the father of Hezekiah,

Hezekiah the father of Manasseh,

Manasseh the father of Amon,

Amon the father of Josiah,

and Josiah the

father of Jeconiah …

at the time of the

exile to Babylon.

Obviously, this is totally

different from our proposed:

Hezekiah = Josiah;

Manasseh = Jehoiakim;

Amon = Jehoiachin ….

Our

exit-clause suggestion: “Amon the father of Josiah”

needs to be amended to read, as according to the ESV Matthew 1:10: “Amos

the father of Josiah”.

“Amos”

(Amoz) would then be meant to indicate - at least according to our revision -

not Amon (“Amos” being a name entirely different from “Amon”), but Ahaz.

Amos (or

Amoz) is a name associated with Amaziah (Abarim

Publications), which name, in turn, at least resembles Ahaziah (= Ahaz).

Allowing

for our duplicate kings, Matthew 1:9-11 could now read as:

…. Ahaz [Amos] the father of Hezekiah [=

Josiah],

Hezekiah the father of Manasseh [=

Jehoiakim],

Manasseh the father of Amon [= Jehoiachin]

… at the time of the exile to Babylon.

With the recognition of these several duplicate kings, then another

problem might be solved. Early kings Joash and Amaziah, omitted entirely from

Matthew’s Genealogy, and whose combined reigns amounted to some 7 decades,

could now be included in Matthew’s list.

The Hezekiah and Josiah

narratives are so similar for the most part as to strengthen the impression

that we are dealing with just the one goodly king of Judah.

Although the 55-year reign of Manasseh

is supposed to have separated Josiah from Hezekiah, one can only marvel at the

fact that Hezekiah, Josiah, have virtually the same lists of priests and

officials.

Previously

we had written on this phenomenon (original version here modified):

"There was

no one like him [Hezekiah] among all the kings of Judah, either before him or

after him." 2 Kings 18:5 (NIV?)

|

"Neither

before nor after Josiah was there a king like him ..."

2 Kings 23:25

(NIV?)

|

The reigns of the pious, reforming kings Hezekiah (c. 716-697 BC,

conventional dating) and Josiah (c. 640-609 BC, conventional dating) are so

alike - with quite an amazing collection of same-named officials - that we need

to consider now the possibility of an identification of Hezekiah with Josiah.

Comparison of Hezekiah and Josiah Narratives

Hezekiah Narrative

2 Chron. 29-32

2 Kings 18-20

Book of Isaiah

|

Josiah Narrative

2 Chron. 34-35

2 Kings 22-23

Book of Jeremiah

|

…

|

…

|

|

|

"There

was no one like him [Hezekiah] among all the kings of Judah, either before

him or after him." 2 Kings 18:5 (NIV?)

|

"Neither

before nor after Josiah was there a king like him ..." 2 Kings

23:25 (NIV?)

|

Jerusalem

to be spared destruction in his lifetime

2 Kings 19:1; 20:2-19; 2 Chron. 32:20,26

|

Jerusalem

to be spared destruction in his lifetime

(2 Kings 22:14-20; 2 Chron. 34:22-28)

|

Revival

of Laws of Moses

"according to what was written"

2 Chron. 30:5,16, 18; 31:2-7,15

|

Discovery

of the Book of the Law (of Moses)

2 Kings 22:8-10; 2 Chron. 34:14-15

|

Passover Celebration

|

Passover Celebration

|

"For

since the days of Solomon son of David king of Israel there had been nothing

like this in Jerusalem."

2 Chron. 30:26

|

"Not

since the days of the Judges (Samuel) who led Israel, nor throughout the days

of the kings of Israel and the kings of Judah, had any such Passover been

observed." 2 Kings 23:22

|

Year

not given

14th day of the second month

|

Year

18

14th day of the first month

|

17,000

sheep and goats, 1,000 bulls

(not including the sacrifices of the first seven days) (1 Chron. 30:24)

|

30,000

sheep and goats, 3,000 cattle

|

Participating

tribes: Judah and Benjamin,

Manasseh, Ephraim,

Asher, Zebulun & Issachar

(2 Chron. 31:1)

|

Participating

tribes: Judah and Benjamin,

Manasseh, Ephraim,

Simeon & Naphtali

(2 Chron. 34:9,32)

|

…

|

…

|

Temporary

priests consecrated for service

|

Employed

"lay people" 2 Chron. 35:5

|

".

smashed the sacred stones and cut down the Asherah poles" 2 Kings

18:4; 2 Chron. 31:1

|

".

smashed the sacred stones and cut down the Asherah poles" 2 Kings

23:14

|

High

places and altars torn down

|

High

places and altars torn down

|

".

broke into pieces the bronze snake"

|

".

burned the chariots dedicated to the sun"

|

Name Comparisons

|

Hezekiah Narrative

|

Josiah Narrative

|

….

|

….

|

|

|

Eliakim

son of Hilkiah, palace administrator

|

Eliakim

"son" (?) of Josiah (future Jehoiakim)

|

Zechariah

(descendant of Asaph)

Azariah, the priest (from family of Zadok)

|

Zechariah

Zechariah

(variant of Azariah)

|

Shaban/Shebna/Shebniah,

scribe

|

Shaphan,

scribe

(son of Azaliah son of Meshullam)

Hashabiah/Hashabniah (2 Chron. 35:9)

|

Jeshua

Isaiah son of Amoz, prophet

|

Joshua,

"city governor"

Hoshaiah (Jer. 42:1; 43:2)

Asaiah, "king's attendant"

Ma'aseiah, "ruler of the city"

|

Jerimoth

|

Jeremiah

son of Hilkiah

|

Conaniah

and his brother Shemei, supervisors

(2 Chron. 31:12)

|

Conaniah/Cononiah,

along with his brothers Shemaiah and Nethanel (2 Chron. 35:9)

Hananiah the prophet, son of Azzur/Azur (Azariah) (Jer. 28)

|

Nahath

|

Nathan-el/Nathan-e-el/El-Nathan/Nathan-Melech

2 Kings 23:11

|

Mattaniah,

Mahath

|

Mattaniah

(future Zedekiah)

|

Jehiel

|

Jehiel,

"administrator of God's temple"

|

Our comment:

Other names could be added to Chart 37, such

as Eliakim son of Hilkiah, the high-priest Joakim of the Book of Judith (for

Hezekiah); and “Jehoiakim the High Priest, son of

Hilkiah” (Baruch 1:7) (for Josiah).

|

|

Shallum/Meshillemoth

(reign of Ahaz)

|

Meshullam

(the Kohathite)

Shellemiah son of Cushi (Jer. 36:14)

|

No

mention of a prophetess

[Our

comment: What about Judith?]

|

Huldah,

wife of Shallam/Meshullam,

prophetess (spokeswoman of the "Lord")

|

Shemaiah

|

Shemaiah

|

Jozabad

|

Jozabad

|

Jeiel

|

Jeiel

|

The author of the article “The Passovers of Hezekiah and Josiah in

Chronicles: Meals in the Persian Period”, for instance, who accepts the

conventional view that Hezekiah and Josiah were two different kings, has

pointed nonetheless to certain similarities:

…. The descriptions of the

Passovers of Hezekiah and Josiah in Chronicles are centralized festivals, held

in Jerusalem and linked in both cases to the feast of Unleavened Bread (2 Chr

30:13, 21 and 2 Chr 35:17) …. In 2 Chronicles 30 this two-week celebration is

followed by various reform activities by all Israel in the territories of

Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim and Manasseh. In Chronicles this festive celebration

forms the climax of the reign of Josiah, followed only by his death at the

hands of Necho. These two Unleavened Bread and Passover feasts enhance the

reputation of two of the Chronicler’s favorite kings, Hezekiah and Josiah.

The meals in both cases are

accompanied by a full array of the clergy …. The addition of the Passover of

Hezekiah and baroque expansion and development of the three-verse celebration

of the Passover of Josiah may conform the story of this eighth and seventh

century kings to the tradition of royal banquets …. Unlike the Persian

banquets, the Passovers of Hezekiah and Josiah in Chronicles were not

characterized by excessive drinking. In fact, alcohol is not mentioned at all.

….

[End

of quote]

Abstract:

Hezekiah and Josiah were the joint authors of unparalleled and

unprecedented religious reforms that found their purpose in Yahweh, and their

presence in Jerusalem. Through dissecting their methods and motivations,

we can begin to uncover the full extent to which their reforming stratagem

converged, diverged, or existed in parallel. Factoring in the

contribution of the Historian and Chronicler, the geopolitical situation,

personal devotion to Yahweh, monarchical relationships with the prophetic

conscience and each king’s lasting historical legacy, we can begin to also shed

light on what role their transformative measures carried out on the macro scale

of Israelite history. ….

[End of quote]

The least reconcilable detail of comparison at this

stage has to be this one:

Hezekiah

Josiah

25 years at

ascension, reigned 29 years

|

8 years at

ascension, reigned 31 years

|

Whilst

we do not have any convincing solution for this one, we can at least say again

that the two-year difference in reign length might be accounted for by a

co-regency.

The

inerrancy of the Bible applies only to original manuscripts, and numbers can be tricky. For example, this is how

the NRSV translates 1 Samuel 13:1: “Saul was . . . years old when he began to

reign; and he reigned . . . two years over Israel.”

And, in the

case of our main character, Amon-Jehoiachin, whereas 2 Kings 24:8 has this: “Jehoiachin was 18 years old when he began to reign,” 2 Chronicles 36:9

says that: “Jehoiachin was 8 years old when he began to reign”. Presumably both

cannot be right.

There is a further complicating factor that Sirach

has separate entries for Hezekiah (48:17-22) and for Josiah (49:1-3), and he

continues on (v. 4) as if these were two distinct individuals: “All

the kings, except David, Hezekiah, and Josiah, were terrible sinners, because

they abandoned the Law of the Most High to the very end of the kingdom”.

On the positive side, there may be yet other

significant advantages to be derived from this new crunching of the era of

Isaiah into the era of Jeremiah.

Isaiah’s father, Micah (refer back to Judith 6:15),

now also becomes a contemporary of the prophet Jeremiah, who will favourably

recall the older prophet. Jeremiah, now threatened with death in the reign of

King Jehoiakim (the son of King Hezekiah as according to our reconstruction)

(Jeremiah 26:1, 8), will tell this of Micah (26:18):

“Micah of Moresheth prophesied in

the days of Hezekiah king of Judah. He told all the people of Judah, ‘This is

what the Lord

Almighty says:

“Zion will be

plowed like a field,

Jerusalem

will become a heap of rubble,

the

temple hill a mound overgrown with thickets”.’

Moreover, the “Suffering Servant” of Isaiah, who

various commentators think most resembles (in literal terms) the prophet

Jeremiah - although we know that Jesus Christ is the most perfect Suffering

Servant - can now be Jeremiah himself as a younger contemporary of Isaiah, and

well-known to the latter (Isaiah 53:2): “He had no beauty

or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should

desire him”. Isaiah,

here, was clearly describing a younger contemporary known to himself and to the

local citizens.

Jesus Christ was not a contemporary who had grown

up before their eyes, though He himself is the quintessential “Suffering

Servant” in the sense that both the Church and Benedict XVI tell of Jesus

perfectly fulfilling the Old Testament and making it new.

“The Atonement of Christ, as both

the eternal high priest and sacrificial victim, not only fulfils the Old

Testament in the sense of transfiguring its symbols into a new reality; it also

gives rise to a new sovereignty, a new kingship”.

Part Two:

Amon

during the Medo-Persian Era

Introductory

section

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The “Artaxerxes” of the Book of Nehemiah was, in fact,

Nebuchednezzar II himself,

meaning that the Medo-Persian era - supposed by

conventional historians to have been

by then a century or more old - was yet some 15 or

more years in the future.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

As with his father, Manasseh-Jehoiakim, our

composite king, Amon-Jehoiachin is scarcely attested during the long reign of

Nebuchednezzar II. The two names emerge in Baruch 1:3-4: “Baruch

read the book aloud to Jehoiachin son of

Jehoiakim, king of Judah, and to all the people who lived in Babylon by the

Sud River”.

Nebuchednezzar II,

perhaps “the basest of men” (Daniel 4:17), and from a barbarous race, would

experience a marvellous conversion (Daniel 4:37), but his son, Belshazzar,

would not. And this has a parallel with Manasseh-Jehoiakim, who ‘humbled himself before the Lord’, while his son, Amon-Jehoiachin

did not. For, as we have read: “Amon increased his guilt”.

Perhaps King Belshazzar, or Evil-Merodach as he was also known – {which name

has nothing to do with Evil, though the king himself had much to do with it} -

recognised a kindred spirit in the Jewish king, because - as we have also read

- the new Babylonian king “graciously freed Jehoiachin king of Judah and

brought him out of prison”. Evil-Merodach did even more than that for Jehoiachin (Jeremiah 52:33):

“He spoke kindly to him and gave him a seat of honor higher than those of the

other kings who were with him in Babylon”. Amon-Jehoiachin was now second-ranked in the kingdom.

And this explains why King Evil-Merodach, or

Belshazzar, making wild promises to Daniel when faced with the Writing on the

Wall, could promise Daniel only third place in the kingdom (Daniel 5:16): ‘If

you can read this writing and tell me what it means, you will be clothed in

purple and have a gold chain placed around your neck, and you will be made the third highest ruler in the kingdom’.

Note that Daniel

says of King Belshazzar (v. 22): ‘But you, Belshazzar [Nebuchednezzar’s] son, have not humbled yourself, though you

knew all this’, precisely what 2 Chronicles 33:23 says of King Amon, “… he did not humble himself before the Lord”.

That was to be the end of King Belshazzar and the

Babylonian kingdom, which would now be superseded by the Medo-Persian kingdom

(Daniel 5:30-31): “That very night Belshazzar, king of the

Babylonians, was slain, and Darius the Mede took over the

kingdom, at the age of sixty-two”.

But it was by no

means yet the end of the second-in-command, Amon-Jehoiachin, who must by now

have been very close in age to the “sixty-two” years of King Darius the Mede.

As for Daniel so

favoured by Nebuchednezzar II, who had lately - despite his protests (5:17): ‘You

may keep your gifts for yourself and give your rewards to someone else’ - been

elevated to third in Belshazzar’s kingdom, his fortunes were on the verge of

skyrocketing (6:3): “Now Daniel so distinguished himself among the

administrators and the satraps by his exceptional qualities that the king [Darius]

planned to set him over the whole kingdom”.

Sadly, though, the

situation became messy between Darius and his administrators and satraps, who

greatly envied Daniel, with the result that Daniel ended up in the lions’ den

(6:16).

Before we can

proceed further with the burgeoning career of Amon-Jehoiachin, now in the

kingdom of Medo-Persia, we need to make the point that the Medo-Persian kings,

and the duration of that kingdom, have been vastly over-extended by the

conventional historians.

This will have

relevance for what is to follow.

Conventional

Persian history lacks an adequate archaeology

The reality (e.g., the archaeological

evidence), is somewhat less than the current ‘history’, with one scholar, H.

Sancisi-Weerdenburg, going so far as to declare that: “The very existence of a

Median empire, with the emphasis on empire, is thus questionable”. (“Was the

ever a Median Empire?”, 1988). The few Medo-Persian kings whom we encounter in

Daniel are far outnumbered by a super-abundant conventional listing (even with

Cambyses omitted):

-

-

-

Artaxerxes

I, king of ancient Persia (464–425 B.C.), of the

dynasty of the Achaemenis

-

Darius

II, king of ancient Persia (423?–404 B.C.)

Tissaphernes, Persian satrap of coastal Asia Minor (c.413–395 B.C.)

-

Mausolus, Persian satrap, ruler over Caria (c.376–353 B.C.)

-

-

The biblical

Nehemiah, Ezra, belonged to the reign of an “Artaxerxes”. But which one?

There can be

fierce debate over whether Artaxerxes I or II is meant.

The big problem is, the “Artaxerxes”

of the Book of Nehemiah was a “king of Babylon”, though he was sometimes found

in Susa - which location was well-known also to Daniel (8:1-2): “In the third

year of King Belshazzar’s reign, I, Daniel, had a vision, after the one that

had already appeared to me. In my

vision I saw myself in the citadel of Susa in the province of Elam …’.

The “Artaxerxes”

of the Book of Nehemiah was, in fact, Nebuchednezzar II himself, meaning that

the Medo-Persian era - supposed by conventional historians to have been by then

a century or more old - was yet some 15 or more years in the future.

Nehemiah, the high

official of the “king of Babylon” was more than likely Daniel himself, serving

Nebuchednezzar. The wall of Jerusalem, just lately destroyed by the

Babylonians, would be quickly rebuilt by Nehemiah after his prudent, wise and

prayerful - indeed most Daniel-like (cf. Daniel 2:14, 18, 27-28) - approach to

the unpredictable king, “Artaxerxes” (Nehemiah 1:11): ‘Lord, let your ear be attentive

to the prayer of this your servant and to the prayer of your servants who

delight in revering your name. Give your servant success today by granting him

favor in the presence of this man. I was cupbearer to the king’.

Having made this

strong point about Medo-Persian ‘history’ (it is only the tip of an iceberg),

our attention can now be focussed again upon Amon-Jehoiachin.

For there is still

some honey to be extracted from that old carcase. (Cf. Judges 14:9)

Amon is

Aman (Haman)

of the

Book of Esther

According to

Esther 3:1: “After

these things King Ahasuerus promoted Haman the Agagite, the son of Hammedatha,

and advanced him and set his throne above all the officials who were with him”.

There is much here, in just this one

verse, requiring to be unpackaged.

“After these things …”. The Persian king,

who had survived an attempted assassination plotted by two of his officials,

but foiled by Mordecai the Jew (2:21-23), had married Esther (1-18).

{The LXX

implicates Haman in the assassination plot}

“King Ahasuerus …”. He is both Darius the Mede, and Cyrus,

and not, as commentators tend to think, Xerxes ‘the Great’ (c. 486–465 B.C, conventional dating) - a largely fictitious

creation of the Greco-Romans, but also a composite mix of real

Assyro-Babylonian-Persian kings (e.g. Sennacherib; Nebuchednezzar II; Cyrus).

“… promoted Haman the Agagite …”. The name “Haman”,

as we once had imagined, must have been the Persian name given to this

character, e.g., “Achaemenes” (Persian Hak-haman-ish).

But we now know its precise origins: Aman (var. Haman) is Amon, an Egyptian

name. It is the name of the captive king, Amon (or Jehoiachin), of Judah.

We shall explain

this further on the next page.

“… the son of Hammedatha …”. Hammedatha was

not the father, as one might immediately be inclined to think, but the mother,

at least the “mother” in that broad sense of the term as discussed in Part One (pp. 3-4).

She was Queen

“Hammutal” (Hamutal), mother of two of Jehoiachin’s uncles, Jehoahaz (2 Kings

23:31) and Zedekiah (24:18).

That makes

“Hammedatha” Haman’s (Jehoiachin’s) aunt, and not his biological mother.

Let us now elaborate on some of these

points.

For a time Daniel (our Nehemiah) - who had

even during the reign of Nebuchednezzar II begun to rebuild fallen Jerusalem,

and who had been raised to third in the Babylonian kingdom only to see Darius

the Mede (= Cyrus = “Ahasuerus”) take the throne and begin to reorganise his

empire (Daniel 6:1-2), and who (as Nehemiah) had returned to Jerusalem in the 1st

year of Cyrus to commence the rebuilding of the Temple - fades into the

background (he may still have been in Jerusalem) to be ‘overshadowed’ in the

biblical narrative by the Benjaminite Jew, Mordecai.

{“The name "Mordecai" is of uncertain origin but

is considered identical to the name Marduka or Marduku …attested as

the name of officials in the Persian court in thirty texts”}: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mordecai

This well-respected Mordecai may possibly

have been the highly-respected and wealthy Jew, Joakim, the husband of the

beautiful Susanna, as recorded in the Book of Daniel. If so, then Susanna -

{said by Hippolytus to have been the sister of Jeremiah} - may well have been

Esther herself, since Jewish tradition claims that Mordecai’s avuncular protection

of Esther (2:7) indicated that Mordecai was actually married to her.

Despite Mordecai’s timely intervention to

save the Persian king from those plotting his assassination - these probably

having been incited by Haman - nothing is done to increase his being honoured

in the kingdom. Instead, Haman takes all the honours, for, as we read above:

“King Ahasuerus … advanced him and set his throne above all the officials who

were with him”. This Haman (Amon-Jehoiachin), who appears to have been -

according to the testimony of Esther, as she prays, a “king” (Esther 4:36-38):

‘And now they are not satisfied that we are in bitter

slavery, but they have covenanted with their idols to abolish what your mouth has ordained, and to destroy

your inheritance, to stop the mouths of those who praise you and to quench your

altar and the glory of your house, to open the mouths of the nations for the praise of vain idols, and to

magnify forever a mortal king’[,]

must have been an

extremely charismatic and competent character for, firstly, Evil-Merodach (as

we read) to elevate him above the rest, and, now, for that Babylonian king’s

successor, Ahasuerus, to do the very same thing for him. As we wrote at the

beginning:

There

must be more to this King Amon of Judah than meets the eye!

And this is borne

out in part by 2 Kings 21:25: “As for the other events of

Amon’s reign, and what he did, are they not written in the book of the annals

of the kings of Judah?”

But now the next

question needs to be answered: If Haman

were, in fact, a Jewish king, why does the Book of Esther call him an “Agagite”

(etc.)? Previously we have written on this:

Haman’s Nationality

This is a

far bigger problem than the traditional view might suggest. Though Scripture

can present Haman variously as an “Amalekite”; an “Agagite” (MT); a “Bougaean”

(Septuagint); and a “Macedonian” (AT) – and though the drama is considered to

be a continuation of the long-running feud between the tribe of Benjamin

(started by king Saul, but now continued by Mordecai) and the Amalekites (Agag

thought to be an Amalekite name, cf. 1 Samuel 15:8) – the problem with this

tradition is that King David had long ago wiped out the Amalekites.

“Bougaean”

is quite a mystery … Haman was certainly a ‘Boogey-Man’ for the Jews.

And

“Macedonian” for Haman appears to be simply an historical anachronism.

Perhaps our

only consolation is that we can discount “Persian” as being Haman’s

nationality, since king Ahasuerus speaks of Haman as “an alien to the Persian

blood” (Esther 16:10).

But what

about a Jew? Surely we can immediately discount any Jewish ethnicity for Haman.

After all, this “alien” was the Adolf Hitler of the ancient world: a Jew hater!

{Though some

suspect that Hitler himself may have had Jewish blood in his veins}.

Surely not Haman,

however? No hint of Jewishness there!

But, wait a

minute. Jewish legend itself is not entirely lacking in the view that Haman may

in fact have been a Jew. Let us read what Louis Ginzberg (Legends of the

Jews) had to say on this, as quoted by another Jewish writer (emphasis

added):

Power

struggle between Jews

….

EUGENE

KAELLIS

Purim is

based on the Book of Esther, the most esoteric book in the Hebrew Testament. ….

Its hidden meaning can be uncovered only by combining a knowledge of Persian

practices during the Babylonian Captivity, the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the

Great, his Edict … and Ginzberg’s Legends of the Jews which … contains a

great deal of relevant and credible history.

Using these

sources, one can arrive at a plausible interpretation completely in accord with

historically valid information. Esther, it turns out, describes an entirely

intra-Jewish affair set in the Persian Empire, with the two major antagonists

as factional leaders: Mordecai, whose followers advocate rebuilding the Jerusalem

Temple, and Haman, also a Jew, whose assimilationist adherents oppose the

project.

Ginzberg

furnishes substantial evidence that Mordecai and Haman were both Jews who knew

each other well ….

[Our comment: They had gone into captivity together (Esther 2:5,

6): “Mordecai

… had been carried into exile … by Nebuchadnezzar … among those taken captive

with Jehoiachin king of Judah”].

From this,

and from some other evidences, a total picture began to emerge. Haman, a king

as we saw – obviously a sub-king under Ahasuerus ‘the Great’ – was none other

than the ill-fated king Jehoiachin (or Coniah), the last king of Judah. Like

Haman, he had sons. But neither Coniah, nor his sons, was destined to rule. The

story of Esther tells why – they were all slain. ….

As for

“Agagite”, or “Amalekite”, it seems to have been confused with the Greek word

for “captive”, which was Jehoiachin’s epithet. Thus we have written before:

Our view now is that the word (of various

interpretations) that has been taken as indicating Haman’s nationality

(Agagite, Amalekite, etc.), was originally, instead, an epithet, not a term of

ethnic description. In the case of king Jehoiachin, the epithet used for him in

1 Chronicles 3:17 was: (“And the sons of Jeconiah), the captive”.

In Hebrew, the word is Assir, “captive” or “prisoner”. Jeconiah the Captive!

Now, in Greek, captive is aichmálo̱tos, which is very much like the word for “Amalekite”, Amali̱kíti̱s. Is this how the confusion

may have arisen?

Haman

the “cut-off” one

Thanks to the continued alertness of

Mordecai, and to the heroic intervention of Queen Esther - a type of Our Lady

of Fatima (today being the 13th of October, 2018) - Haman the

(Hitlerian) Jew’s “Final Solution” plan to exterminate all of the people of

Mordecai, who had refused to bow the knee (proskynesis)

to Haman (Esther 3:2), was brilliantly turned on its head due to the Lord’s

‘rival operation’.

Had not the Book of Jeremiah early

predicted this, it even cutting short the name of Jehoiachin (or Jeconiah), to

render it as “Coniah” (Jeremiah 22:24-30)?:

‘As

surely as I live’, declares the Lord, ‘even if

you, Coniah son of Jehoiakim king of Judah, were a signet ring on my right

hand, I would still pull you off. I will deliver you

into the hands of those who want to kill you, those you fear—Nebuchadnezzar

king of Babylon and the Babylonians. I will hurl you and the

mother who gave you birth into another country, where neither of you was born,

and there you both will die. You will never come back

to the land you long to return to’.

Is this man Jehoiachin a despised,

broken pot,

an

object no one wants?

Why will he and his children be hurled out,

cast

into a land they do not know?

O land, land, land,

hear

the word of the Lord!

This is what the Lord says:

‘Record this man as if childless,

a

man who will not prosper in his lifetime,

for none of his offspring will prosper,

none

will sit on the throne of David

or

rule anymore in Judah’.

This is how Jehoiachin, as Amon,

came to die – and it was a violent death (2 Kings 21:23): “Amon’s officials

conspired against him and assassinated the king in his palace”.

It bears favourable comparison

to the violent death of Haman, also in his palace (or “house”) (Esther

7:8-10):

As soon as the

word left the king’s mouth, they covered Haman’s face. Then

Harbona, one of the eunuchs attending the king, said, ‘A gibbet reaching to a

height of fifty cubits stands by Haman’s house [palace]. He had it set up for

Mordecai, who spoke up to help the king’.

The

king said, ‘Impale him on it!’ So they impaled Haman on

the pole he had set up for Mordecai. Then the king’s fury subsided.

What the Book of Esther does not

tell us, but we find it in the account of the violent death of King Amon (2

Kings 21:24): “Then the people of the land killed all who had plotted against

King Amon …”. For the conflict between the Haman-ites, “the people of the land

[of Susa]”, and the loyal Jews, had not fully been resolved with the death of

Haman.

It, like Fatima, was awaiting a

13th of the month fulfilment, “… the thirteenth day of the twelfth

month, the month of Adar” (Esther 9:1).

Only then do we find that (vv. 5-12):

The Jews struck down all their

enemies with the sword, killing and destroying them, and they did what they

pleased to those who hated them. In the citadel of Susa, the Jews killed and

destroyed five hundred men. They also killed Parshandatha, Dalphon, Aspatha,

Poratha, Adalia, Aridatha, Parmashta, Arisai, Aridai and Vaizatha, the ten sons

of Haman son of Hammedatha, the enemy of the Jews. But they did not lay their

hands on the plunder.

The number of those killed in the

citadel of Susa was reported to the king that same day. The king said to Queen

Esther, ‘The Jews have killed and destroyed five hundred men and the ten sons

of Haman in the citadel of Susa. What have they done in the rest of the king’s

provinces? Now what is your petition? It will be given you. What is your

request? It will also be granted’.

Queen Esther, no doubt well aware

of what Jeremiah had foretold of Haman (as “Coniah”), and not wanting any of

his seed left alive to rule over the Jews, seems to go into overkill here (v.

13-14): “‘If it pleases the king’, Esther answered, ‘give the Jews in Susa

permission to carry out this day’s edict tomorrow also, and let Haman’s ten

sons be impaled on poles’. So the king commanded that this be done. An edict

was issued in Susa, and they impaled the ten sons of Haman”.

Daniel

9:26’s “And

after the sixty-two weeks, an anointed one shall be cut off and shall have

nothing” must surely refer to the “anointed” (that is, ruler), King Amon, now

“cut off” (dead) and having “nothing” - “none of his offspring

will prosper” - all of his ten sons impaled!